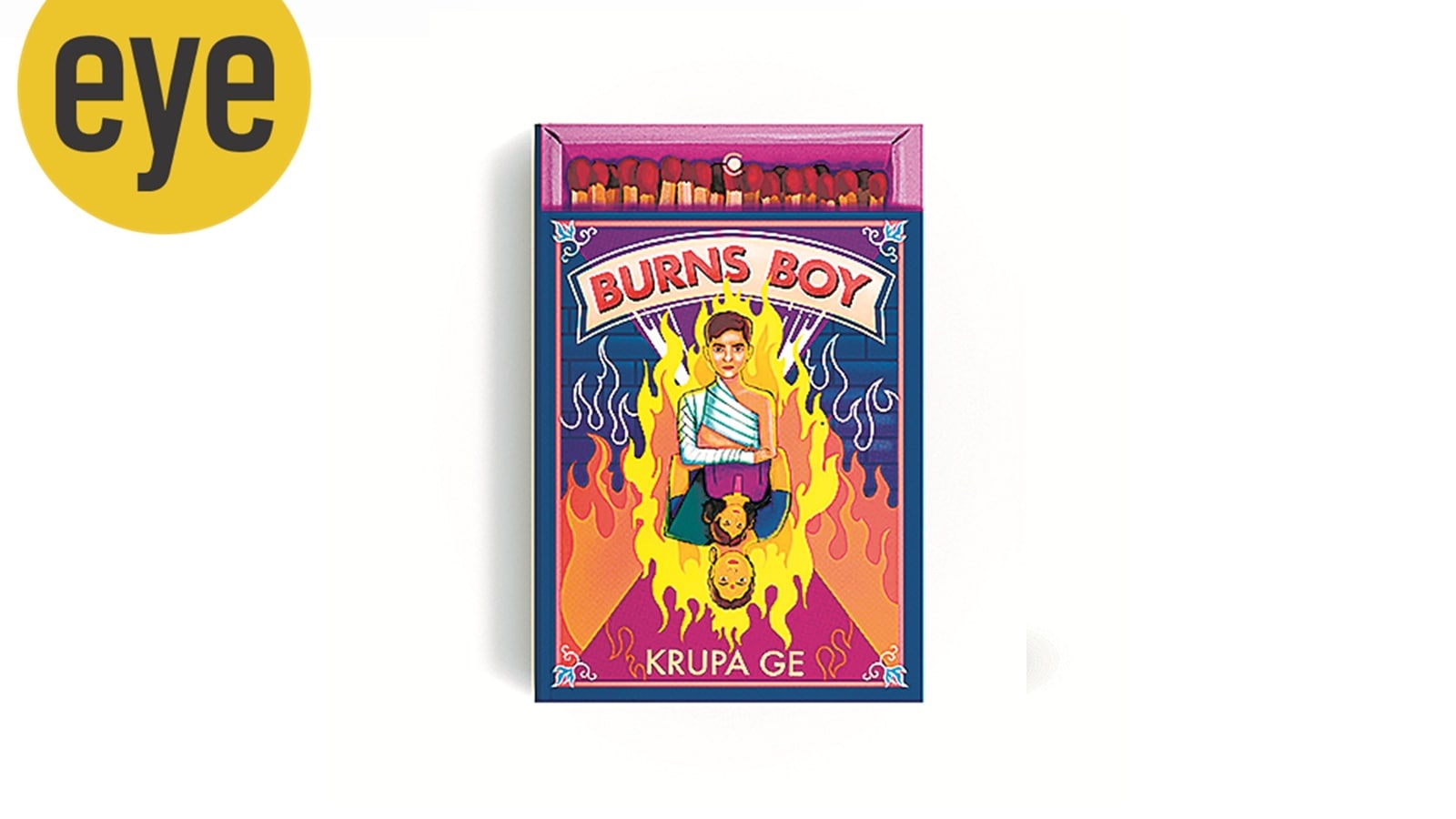

A teenage boy lies in a ward filled with victims of burn injuries — dowry burns, acid attacks and more. He is the only anomaly in the ward. This is where Krupa Ge’s Burns Boy begins, pulling readers into a family’s story seared by accident and silence.

Set in 1990s’ Chennai, the story unfolds through three voices — Guru, his mother and his sister Aparna — each with their own memory of the events leading up to the boy being admitted to the hospital. Guru, the “burns boy”, is both a victim and a witness. His anger smoulders beneath his skin as he accuses his mother of neglect and emotional absence. Aparna carries a quieter pain, haunted by guilt and invisibility. Their mother, a government employee and aspiring writer, navigates exhaustion, self-doubt and the burden of being blamed for everything.

Ge structures the novel like a set of testimonies where each character’s recollection deepens but never clarifies. What actually caused the fire is not the main matter, it is more about how the family carries the scars of the event. There is no direct truth, no sweeping backstories and no omniscient explanations. Instead, like human memory, the story is fragmented; the details blurry.

The burns ward becomes a striking metaphor for gendered suffering. Ge uses that setting to examine what it means to heal within a structure that expects women to endure and men to recover. The writing is tactile. The author’s meticulous research into burn treatment lends authenticity to the narrative. Readers can almost feel the heat, the clinical sting, the claustrophobic intimacy of hospital air.

Burns Boy, however, is not merely a medical or tragic novel. It is an intimate exploration of how love coexists with resentment, how guilt binds families tighter than affection. The fire becomes a prism through which class, gender and generational expectations refract. Guru sees his mother’s independence as betrayal; Aparna sees it as fragile bravery. Their mother wonders if a “good mother” even exists.

Time, too, burns differently for each of them. As a young girl, Aparna hated her mother spending time far away from her, only to empathise with her once she became a mother herself. But the trauma never disappears — it merely changes form.

The novel’s rhythm mirrors its themes. Short, precise sections replace traditional chapters. It slips between internal thoughts and clipped observation, creating a sense of constant watchfulness. This ensures no voice dominates; everyone carries guilt, everyone hides something, making it difficult for the readers to pick a side.

Story continues below this ad

Ge does not take you on a sightseeing trip around the yesteryear’s Chennai. Instead, she brings in texture through the smell of bakeries, the quiet bureaucracy of government offices, the languid afternoons of a pre-internet childhood.

What distinguishes Burns Boy from a lot of other contemporary fiction is that there is no moral lesson, no catharsis. The characters feel emotions in layers, like any other person you know. It refuses to take a side. The title of the novel might be Burns Boy but the story is as much of Guru’s amma and Aparna as it is of the titular character. Guru can be cruel, his mother defensive, Aparna detached — and yet it is their flaws that make them achingly real.

By putting a boy and the women around him at the centre of the tale, Ge examines how patriarchy shapes even victimhood — how empathy is rationed differently between genders. The burns on Guru’s body are visible; the ones on his mother’s psyche are not. The emotional impact lies in how little the book resolves. There is no magical solution to familial problems. Instead, the novel insists that pain has multiple witnesses and that healing is not a single act but a lifelong negotiation.

In the end, Burns Boy reads like a family archive where each page is fragile, each truth incomplete. It is a novel about survival, yes, but also about the human instinct to narrate pain until it makes sense.