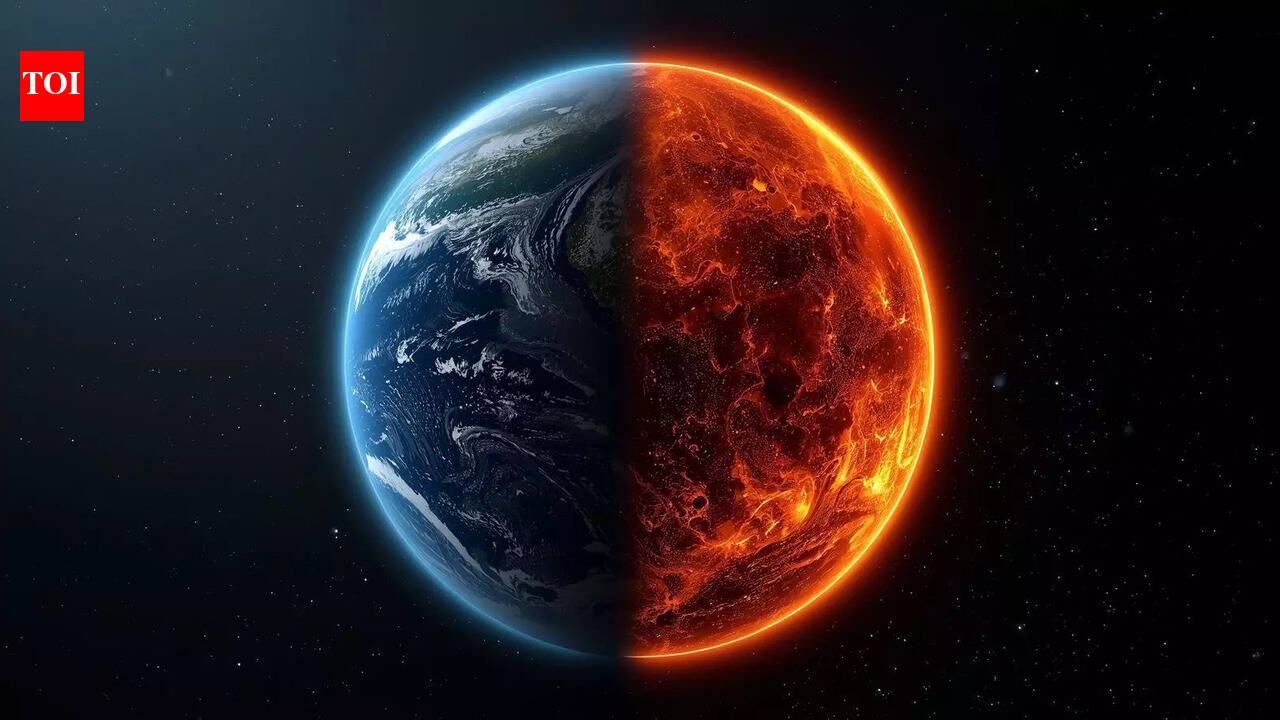

Astronomers have spent the past decade cataloguing thousands of planets beyond the solar system, many of them falling into a strange middle category. These worlds, known as sub Neptunes, are larger than Earth but smaller than Neptune, and they appear everywhere modern telescopes look. From a distance, they seem promising. Their sizes and atmospheres have even fuelled speculation about vast oceans hidden beneath thick layers of gas. But new research suggests that picture may be misleading. Instead of calm, water-rich worlds, most of these planets may still be intensely hot, with molten rock dominating their interiors. The shift does not rely on new observations, but on a different way of interpreting data astronomers already have.

Worlds believed to hold oceans are now suspected to be lava dominated

Sub Neptunes are the most common type of exoplanet detected so far, yet they remain poorly understood. Measurements usually give scientists only a planet’s radius and mass. From that, several internal structures can fit the same data. A planet might have a deep ocean under a hydrogen atmosphere, or a rocky interior wrapped in gas. Both can look identical from Earth. This uncertainty is known as degeneracy, and it has shaped much of the debate around potentially habitable worlds beyond the solar system.

Gas dwarfs offer a simpler explanation

One long standing idea is that many sub Neptunes are gas dwarfs. In this picture, the planet has an Earth like core made of silicates and iron, surrounded by a thick hydrogen dominated atmosphere. These planets would have formed extremely hot. The question has always been whether they cooled enough over time to become solid inside. That detail matters, because a solid planet and a molten one behave very differently, especially when it comes to their atmospheres.

Molten interiors change atmospheric chemistry

If a planet has a global magma ocean, the molten rock does not stay isolated. It interacts with the atmosphere above it, absorbing and releasing gases. This can affect chemical markers such as methane, carbon dioxide and ammonia. In earlier studies, the lack of ammonia in some exoplanet atmospheres was taken as a sign of liquid water, since water absorbs ammonia efficiently. The new work points out that molten rock does much the same thing. The same atmospheric signal can come from a lava world.

The solidification shoreline reframes the problem

To explore this, researchers introduced a concept they call the solidification shoreline. It links how much energy a planet receives from its star with the star’s temperature. Using a coupled interior and climate model known as PROTEUS, they simulated how long magma oceans can last. When known sub Neptunes were plotted against this framework, almost all of them fell on the hot side of the boundary. About 98 percent appear to receive enough energy to stay molten even today, assuming they are gas dwarfs.

Hycean worlds lose ground

The research “Most Rocky Sub-Neptunes are Molten: Mapping the Solidification Shoreline for Gas Dwarf Exoplanets” challenges the idea of hycean planets, which are thought to host deep oceans beneath hydrogen rich skies. A well known example is K2 18b, once described as a strong ocean candidate. The new interpretation does not rule out water entirely, but it suggests molten interiors offer a more straightforward explanation based on physics rather than chemistry alone. Some combinations of mantle composition and atmospheric carbon could shorten magma ocean lifetimes, but those planets would likely not match the observed sizes of sub Neptunes.

Implications for life and future studies

For researchers searching for life, the result is sobering. Lava dominated worlds are unlikely to be friendly environments. Yet the work provides a clearer footing for future studies. It highlights how limited current atmospheric data still is and how easily hopeful interpretations can form. Rather than closing the door on ocean worlds, the study narrows the field. It suggests many of the planets we once imagined as water rich may instead be places of enduring heat, quietly reshaping how scientists think about common planets in the galaxy.