On February 3, Andhra Pradesh and Assam borrowed Rs 1,100 crore and Rs 1,000 crore respectively through auction sales of 15-year state government securities at an average yield or interest rate of 7.66%.

One year ago — on February 4, 2025 — the two states had paid only 7.15-7.16% at the auction of securities with the same 15-year tenor that raised Rs 2,000 crore and Rs 900 crore respectively.

The story wasn’t different for the Gujarat government that, on January 27, mobilised Rs 2,000 crore via a 10-year security sale at an average yield of 7.45%. In a year-ago auction of the same security on January 28, 2025, the state government mopped up Rs 1,000 crore at just Rs 7.02%.

To put these into perspective, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has, since February 6, 2025, cut its benchmark policy repo rate from 6.5% to 5.25%. But this reduction — in the rate at which it provides overnight (i.e. one-day maturity) loans to commercial banks — hasn’t led to any lowering of borrowing costs for state governments.

On the contrary, state governments are today paying 0.4-0.5 percentage points more to borrow for 10-15 years than what they were last year at this time.

Moreover, it isn’t the states alone. In the last one year, yields of 10-year Government of India securities, too, have risen from 6.66% to 6.73%, notwithstanding RBI’s key lending rate coming down by 1.25 percentage points over this period.

Why are governments paying more despite RBI’s rate cuts?

There are two main reasons for that.

Story continues below this ad

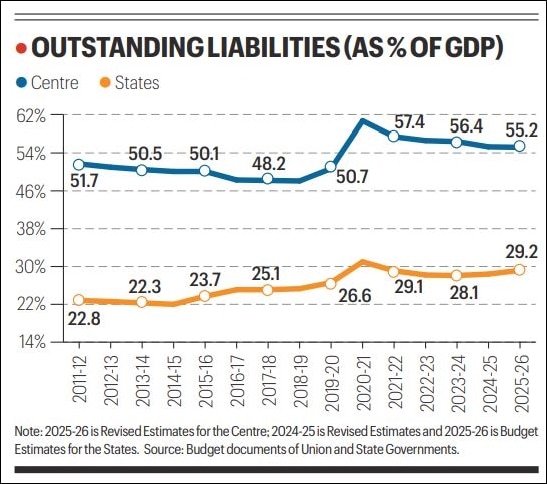

The first is structural, having to do with the sheer scale of borrowings by both the Centre and the state governments. The accompanying chart shows their outstanding liabilities — basically debt, on which interest is payable along with the principal amount — as a percentage of India’s gross domestic product at current market prices.

The Centre’s outstanding debt-GDP ratio fell from 51.7% to 48.1% between 2011-12 and 2018-19. An economic growth slowdown in 2019-20, followed by the expansionary fiscal response to the Covid-19 pandemic-induced disruptions, led to a spike in the ratio to 60.7% in 2020-21. There has been a modest drop since then, to 55.2% in 2025-26 and a budgeted 54.7% for the coming fiscal year ending March 31, 2027.

It has been somewhat different for the states, with their consolidated debt actually increasing from 22.8% in 2011-12 before peaking at 31% in the 2020-21 Covid year. Thereafter, it has only gradually declined to 29.2% in 2025-26. This is a far cry from the debt-GDP targets of 40% for the Centre and 20% for the state governments combined by 2024-25, set under the 2018 amendment to the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management Act, 2003.

The rising debt levels have, first of all, resulted in ballooning interest payments. These amounted to Rs 12.74 lakh crore or 38.1% of the total revenue receipts (i.e. income) for the Centre and a budgeted Rs 6.25 lakh crore or 12.2% for the states in 2025-26. Secondly, just as interest payments are consuming a large share of their budgets and eating into other expenditures, government borrowings tend to “crowd out” private borrowings, thereby driving up rates in the money market.

Story continues below this ad

The Centre alone has budgeted gross market borrowings of Rs 19.70 lakh crore for 2026-27, as against Rs 16.19 lakh crore and Rs 15.47 lakh crore for the preceding two fiscals. Even after deducting repayments, net borrowings are pegged at Rs 11.73 lakh crore, up from Rs 10.40 lakh crore in 2025-26 and Rs 10.75 lakh crore in 2024-25.

What is the second reason for the current situation?

It has to do with liquidity.

Excessive government borrowings may not cause much “crowding out”, when there is enough economic slack and liquidity in the system.

This was, indeed, the case in the last many years, when private sector investment and the attendant credit demand was lacklustre. On top of it was the abundant supply of liquidity from foreign capital inflows that, in net terms, averaged over $75 billion annually between 2017-18 and 2023-24. As the RBI bought up the surplus dollars gushing in and added to its foreign exchange reserves, it also ended up injecting rupee liquidity into the banking system.

That has, however, changed from 2024-25. Net foreign capital inflows were at only about $18 billion that fiscal and at $8.6 billion during April-September 2025. Foreign portfolio investors alone pulled out $18.9 billion from Indian equity markets in 2025 and another $3.1 billion in this calendar year so far. Unlike earlier, when it was sucking up dollars and accumulating forex reserves, the RBI has been doing the opposite to prevent an uncontrolled depreciation of the rupee. But while selling dollars from its kitty, it has simultaneously drained rupee liquidity from the system.

Story continues below this ad

The end-result is that just when a recovery in private sector credit demand, if not investment, seems underway, there is a hardening of interest rates from a tightening of liquidity. The markets haven’t also taken kindly to the government’s borrowing programme; it is perceived as too large in the present scenario where liquidity isn’t plentiful.

That applies not only to the domestic market: With 10-year government bond yields at nearly 4.25% in the US and 2.25% in Japan, there is no cheap global money sloshing around either like before.

Not for nothing the RBI’s repo rate cuts have had “limited transmission”, to use financial jargon. While its policy lending rate has fallen by 1.25 percentage points since last February, commercial banks have lowered rates by an average of 1.05 percentage points on fresh loans and 0.95 percentage points on term deposits. This, even as the cost of borrowings for the government — both the Centre and states — has gone up.

Liquidity tightening could become a real problem if investment sentiment revives, especially with fructifying of the bilateral trade agreement between India and the United States. The hope is that it would also stimulate the return of foreign portfolio investors. Their pouring money into Indian markets after an extended phase of selling will definitely help ease the current liquidity concerns, among other things.