Shiba Marndi says “thoda gadbad” (a little mishap) happened right after he was born in Odisha’s Mayurbhanj district. It’s more grave. His parents, he later explains, “abandoned” him. But his mother’s elder sister, his “badi maa”, brought him to the outskirts of Bhubaneswar and took him in. Raising four of her own, the family didn’t have any comforts to offer him.

But he’ll never forget how, years later, she encouraged him to get back on his feet after a nasty tackle on his chest left him struggling to breathe for six months. “She has never seen my sport. But she knew how happy I was playing it. After I had recovered from the chest-hit, she told me, ‘Don’t take tension, ja khel. Bas dekh ke khel (go play, just play safe). I’m with you’,” he says.

The sport — one that has given many aimless youth a frenzied direction in life — is Aussie rules Footy or simply ‘Footy’. In the roughly two decades since the sport was introduced in India, while Footy has taken firm root in some of tribal areas of Odisha and Jharkhand, it has also drawn into its orbit players from some of the most dire areas — from the urban slums of Mumbai to migrant labour colonies in Rajasthan, from nondescript villages in Andhra Pradesh to the border belts of West Bengal and the struggling shanty villages of Bihar.

Over 250 men and around 50 women from 11 states participated in the recently concluded Ranchi Nationals, where the Jharkhand Crows teams took all the three titles — Senior Men’s, Senior Women’s and Junior’s.

Players from the Jharkhand team practise at a ground in Ranchi. (Express photo by Shubham Tigga)

Players from the Jharkhand team practise at a ground in Ranchi. (Express photo by Shubham Tigga)

If rugby liberated footballers who felt constricted by the dribbling, Footy is for those who love to run unhindered and play a mix of basketball, volleyball and football. It helps that at least for those 80 minutes of kicking, handballing and running with the ball, the game distracts from the desperate realities of their lives.

“I used to play cricket and football, like the father who left me. But in cricket you had to wait for the ball and stand till then. Footy, every minute you have to move,” says Marndi, who captained the Odisha Swans side that finished as semifinalists. “Had it not been for my badi maa, I would never have made the India team. She was worried for six months after my injury, but then the courage, too, came from her.”

Two things established Jharkhand as the prime force to AFL boss Andrew Dillon — when they kicked, they did so straight with the top of the foot, and they knew how to hold the ball vertically

Marndi’s biggest achievement was to make it to the Indian team six years ago. Every three years, the team, called the ‘Indian Tigers’, travels to Australia for the AFL International Cup — the World Cup of the sport. Led by Jharkhand’s Mahesh Tirkey, who currently works in Jamshedpur as a District Sports Officer, the team has players mainly from Jharkhand and Bihar, the two finalists in the recent Nationals, but there are others from Maharashtra, Odisha, West Bengal and Rajasthan too.

Story continues below this ad

A foothold in India

Footy is as dear to Aussies as the beach and surfing, but the only one with cultural heft that can be exported.

The Australian Football League (AFL), with 19 club teams from across four Australian states, plays Footy as a winter sport, with grounds shared with cricket, the country’s summer sport. Many of the top cricket venues in the country such as the Melbourne Cricket Ground, Sydney Cricket Ground and Adelaide Oval host both sports with drop-in pitches for cricket.

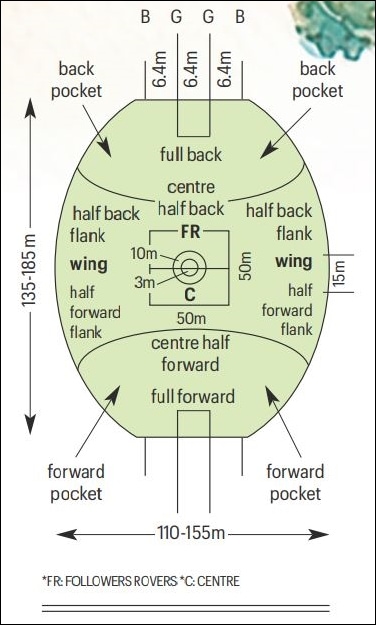

A high-energy contact sport, Footy sees 18 players a side crisscrossing a giant oval field, with their goal being to score in the trapezoid-shaped goal zone that’s marked by vertical posts or uprights. While the sport has assumed the following of the country’s unofficial religion — with Footy team loyalties worn as identities — the sport hasn’t quite managed to find takers outside Australia. The AFL tried to get the sport into China, and sought out the US (including Las Vegas) and parts of northern England, but didn’t make any headway.

And then, sometime in 2004-05, at the height of MS Dhoni’s emergence from Jharkhand, Footy coaches from Australia landed in the state’s tribal districts and flung the funny oblong ball at anyone who peered at the strange-looking mish-mash sport.

Story continues below this ad

But like every sport looking to take off in India, Footy needed a toehold in Kolkata, a city with a deep sporting culture, organisational heft and an amateur athlete base willing to try out new games. It’s here that cricketer Ricky Ponting launched an initiation programme for Footy when he was at Kolkata Knight Riders.

Soon after, around 150 volleyball, basketball, high jump and rugby athletes from West Bengal were trained in the basics of Footy. Some from among the 150 then fanned out across the tribal belts of West Bengal, Bihar, Jharkhand and Odisha, while a few took the sport to Magic Bus, a sports NGO in Mumbai. The NGO took it further into Maharashtra (mostly Mumbai’s slums and Navi Mumbai’s developing areas) and to Rajasthan, mainly to Jaipur’s unstructured playing grounds. And then, just like that, the ball got rolling.

Neetu, an economics student in Ranchi, works as a domestic help after college. “Footy has given me a different identity. It will be a struggle. But we are ready to struggle,” she says

But what got AFL big boss Andrew Dillon intrigued enough to travel to Jharkhand for the recent Nationals was the official AFL registration number of 10,000. These were players who had over the last decade played Footy in some form or trained in the sport. Everything scales up in India, but Dillon merely wanted to see those large numbers and assure himself that this highly-difficult-to-transplant sport could proliferate in a foreign land.

Effort and money from Australia had, of course, trickled in over 11 years to spread the game, and teams such as Jharkhand Crows, Kerala Bombers and Bengal Tigers and Maharashtra Giants had ripped off jersey designs and names from Australian teams such as Adelaide Crows, Essendon Bombers, Richmond Tigers and GSW Giants.

Story continues below this ad

While the sport is yet to be recognised by the government or the Sports Authority of India, it offers players a chance to get into state teams and play for India, all under AFL funding. AFL also funds volunteering coaches to bear expenses towards the annual Nationals.

As he watched the players in Ranchi, two things established Jharkhand as the prime force to Dillon straightaway — when they kicked, they did so straight with the top of the foot, and they knew how to hold the ball vertically, like it ought to be.

In the early setting winter sun, a group of players in blue Jharkhand jerseys noisily chase an oblong ball, as coach Ravi Minj watches through the haze of dust they have kicked up.

At the first whistle for break, Neetu Kumari walks up to the edge of the field and slumps to the ground to pull up her socks. A 20-year-old from the Munda tribe, she has grown up playing football, but it’s in Footy that she sees her future. She doesn’t have to look too far for inspiration — Jharkhand’s Aloman Tigga is considered a pioneer in women’s Footy.

Story continues below this ad

Neetu, an Economics (Honours) student at Doranda College in Ranchi, works as a domestic help after college, earning around Rs 2,000 a month. “This game has given me a different identity. It’s not very well known outside Jharkhand, so it will be a struggle. But we are ready to struggle,” she says.

For coach Minj, a former footballer who has been coaching the state team since 2014, the struggle begins even before they reach the ground. He says a couple of years ago, the ground they trained on was acquired by a PSU, forcing them to practise on an uneven, open ground in Ranchi. “The earlier ground gave us a very positive vibe. People from the nearby slum areas would sit and cheer for us. That encouraged us a lot,” he says.

But when he watches his boys and girls playing — the perfect top-of-the-foot kick, just the right grip of the ball — he knows they have it in them.

Australia-based cricket writer Bharat Sundaresan, who the AFL consults on its Indian outreach programmes and who accompanied Dillon to Ranchi, says Footy’s growth in India has been organic. “It’s a unique way of growing this sport as an indigenous one, where most players have never watched an Aussie Footy game or can’t name a player,” he says.

Story continues below this ad

‘Khel matlab nikamma’

India captain Tirkey, who played dodgeball while in Madhubani, Bihar, settled in Ranchi after the death of his father, a railway employee, in 2005. He was among the earliest of athletes from Jharkhand’s tribal families whose natural strength and running made them take on the role of ‘small forwards’ and run freely in a sport that has no offside rule.

Their athleticism supported the sport’s free spirit. No Jharkhand junior team has ever lost a final in India, even as seniors are serial champions, says Footy’s India chief and former captain, Sudip Chakravarthy.

Arun Rai is from Kaimur in Bihar, a Footy state that goes under the radar only because it is overshadowed by Jharkhand. However, he grew up in Jaipur, living with his uncle and aunt (“kaka aur kaki”). They had moved in search of employment, taking the young Arun with them so he could access better education.

The pressure of academics on children of Bihar migrants is stifling, he recalls. His uncle never forgot to remind him that he had walked 1,500 km from Kaimur, and only Arun’s academic success was worth that sacrifice. But he hated to study and Footy was his release. It was while playing football in Jaipur that he spotted Footy players trained by one of the 150 initial apostles from Magic Bus. A friend persuaded him to join, and he was smitten for life, given how much he loved to run.

Story continues below this ad

“Khel matlab nikamma (You are worthless if you play) is the Bihar mindset,” he says. “It’s worse in my case because I lived in a joint family and had moved to Jaipur with my uncle, and was expected to prove that moving out was worth it. Nobody in my family had ever played sports, and after Class 12, you either started preparing for competitive exams or joined the Army or CRPF. When I said I wanted to play a sport, let alone Footy, it was a scandal,” he recalls.

Cricket — and an empathising aunt, his kaki — helped. “It’s not like she knew what Footy was, but she was mad for cricket. When I told her Harbhahan Singh became DSP by playing sport, and the Great Khali also landed a police job, she went about convincing my uncle because it’s about financial independence,” recalls the captain of Bihar Bulldogs who works as head coach at Rajasthan’s biggest residential university, Banasthali University in Tonk.

“Once I broke my foot. The shouting and the scene that followed at home! They declared my sport over,” he says.

Once again, the kaki prevailed. It helped that Footy offered up to Rs 1.5 lakh as medical insurance back then.

Story continues below this ad

He might have taken to Footy fleeing his disinterest in academics, but Rai ensured he completed his coaching certification courses and earned a degree. “I completed a Master’s in physical education. I’m a Bihari, I know how important education is,” Rai laughs.

‘Imagine playing for India’

Back in Australia, Footy has struggled to lure the Indian diaspora despite many outreach attempts. The sheer physicality drives most of them to the safer, softer cricket.

Chakravarty, the AFL India head, points out that most Footy balls get stitched in Jalandhar, Punjab. That, to him, is a sign, along with the sport’s success in Jharkhand, that Footy might take off faster in India than it has among Indian-origin Australians.

That dream looms large in Maharashtra Giants’ captain Amos’ eyes. Keeping with how Footy winds up finding just the ones who need that turbocharging to their dreary lives, the sport reached Amos at Mumbai’s Govandi slums and then followed him into Navi Mumbai, where he built his first concrete home. A sports lover, cricket had snapped his shoulder, football broke his elbow, but Footy kept him away from crime and drugs. “When inside the ground, all pain vanishes with the whistle. Life is tough, but imagine getting to play for India. We apply spray and run freely,” he says.

It was his mother’s support, he says, that made a “fighter” out of him. “Our team has bankers, airline groundstaff, tailors, factory labourers. We represent not just the state, but our families, the mothers who teach us to be brave and go out there without fear of getting hurt,” he says.

His reward? “When passersby at Shivaji Park stop to see us play. And stay there and keep watching. That look on their faces… it’s priceless.” He knows his mother, who’s barely seen Australian Footy, will be proud.

Rules of the game

- Footy combines elements of basketball, volleyball, rugby, handball, soccer

- It’s a high contact and physically demanding sport, with full-body tackles and collisions between players, who run for almost 12-15 km per game. But in India, it’s played with restricted tackles

- There are two ways of moving the ball forward — handballing and kicking with a straight (top of the) foot. To handball or punch the ball, players hold the ball in one hand, clench the fist of the other, punch the ball with the clenched fist and release the ball. Rucks (jumping to gather aerial balls like in basketball) are manned by specialists, usually the tallest members

- Scoring happens when the ball clears the zone of the forward posts (the two upright bars). You score six points if they go past the two smaller back posts and 1 point if the ball lands in from sideways. So if a team scores 3 outright goals (3×6=18) and 5 (5×1) through the side bars, they end with 23 points

—With inputs from Shubham Tigga