There are certain bodies that move through the world under a quiet assumption of availability. Their presence is noticed, assessed, and often consumed. For women, this experience is neither incidental nor exceptional. It is learned early, reinforced socially, and sustained through material inequality. What appears as desire is often entangled with less visible forces — insecurity, hierarchy, and the uneven distribution of power.

In such a context, sexual exploitation cannot be understood as a series of isolated acts spoken about separately, as if it began and ended there. What disappears in this way is the larger picture. The same conditions repeat themselves: Money, access, silence, protection. Some people are able to move freely, others are left to deal with what happens to them alone. Women’s bodies are used again and again, but the use is never named together. The focus remains on particular acts or individuals, while the broader conditions that make women’s bodies available remain unchanged. Exploitation, in this sense, is not an accident within the system; it fits into it.

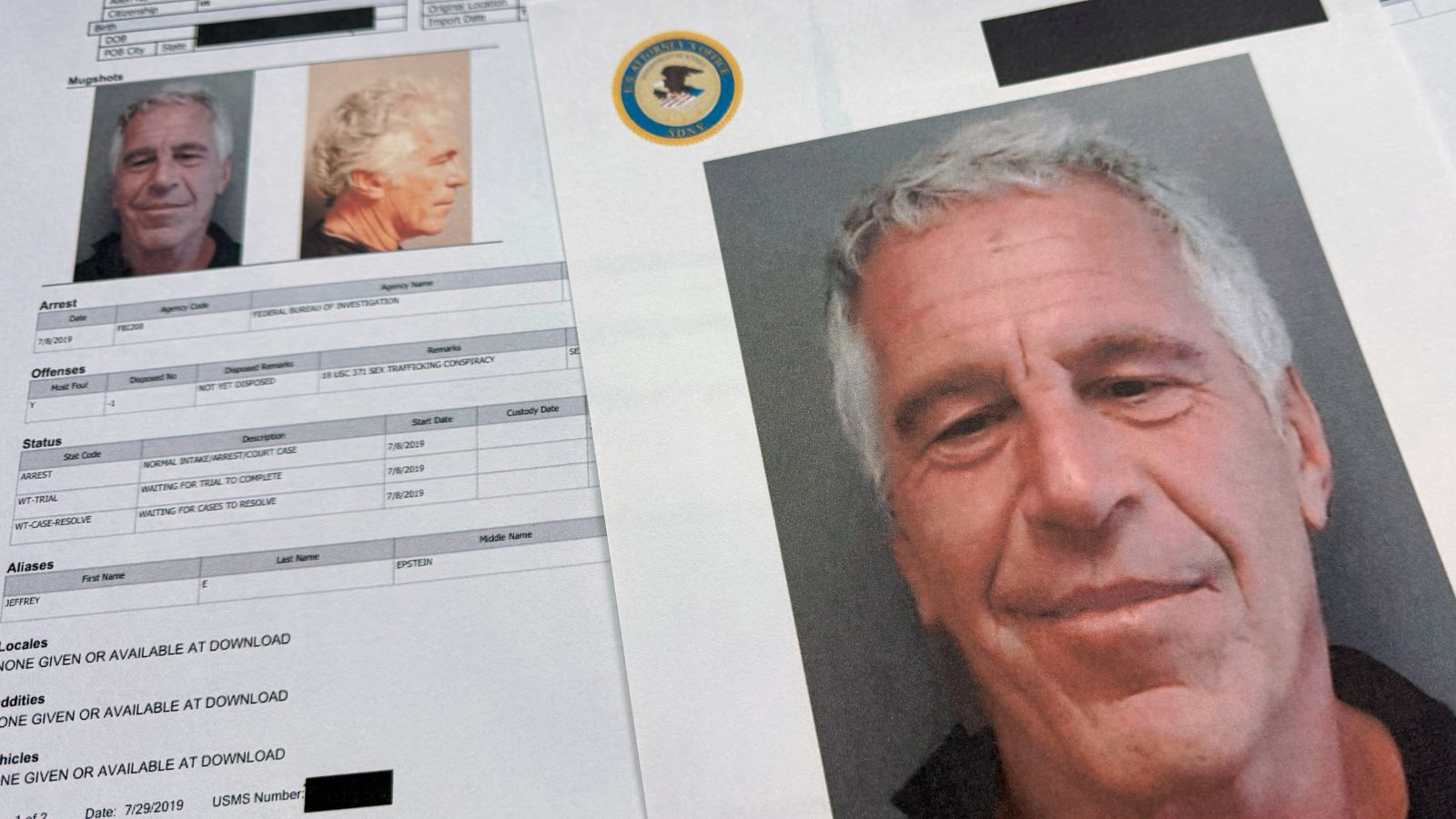

The Epstein Files make this arrangement briefly visible. Not because they reveal an unprecedented form of violence, but because they expose how easily sexual exploitation can be organised, mediated, and sustained within elite networks. They reveal a structure capable of absorbing exposure without collapsing. This is how capitalism works as a way of organising life. It works through inequality. It persists because it is embedded in economic dependence, legal discretion, and institutional priorities that protect markets more readily than they protect women. What remains intact after exposure is not merely power, but the logic that organises it. Women’s bodies continue to be treated as available, replaceable, and manageable, while accountability is distributed along familiar lines of class and status.

Crucially, this process is not evenly distributed. Not all women are commodified in the same way, nor to the same degree. Class, race, caste, nationality, and age determine whose bodies are rendered most disposable and whose exploitation is most easily justified. The market does not operate blindly; it is calibrated. Some bodies are spoken of as “fresh,” revealing a logic that treats women not as people but as consumable objects. Seen this way, the commodification of women’s bodies is not a moral failure that can be corrected through better behaviour or harsher penalties. It is a structural outcome of an economic order that relies on inequality to function. As long as women’s security remains conditional and power remains concentrated, the market will continue to find ways to extract value from women’s bodies—legally, culturally, and with institutional support.

Sexual exploitation is condemned when it becomes visible, but the consequences of that condemnation do not move evenly. Those with less power can be more easily framed, investigated, and punished, while others remain beyond reach. What remains unaddressed are the economic and social arrangements that allow women’s bodies to circulate as resources. In this way, justice absorbs critique without transforming itself. These conditions do not end at the moment of violence; they shape the broader field in which sexual relations occur. When access to security, housing, work, and protection is uneven, power is already present before any interaction begins. What is at stake, then, is not simply better accountability, but a different way of thinking about sexual relations themselves.

It is in this context that arguments like those advanced in Why Women Have Better Sex Under Socialism become useful — not as a blueprint or an ideal, but as a provocation. Ghodsee’s work does not claim that socialism resolves sexual violence, but it insists on a crucial insight: Sexual freedom cannot be separated from material conditions. As long as inequality structures access to security, the language of consent will remain fragile, and justice will remain reactive. Read this way, the Epstein Files do not simply expose the abuse of power; they reveal the poverty of our existing frameworks of justice. They show how easily punishment can coexist with commodification, and how readily outrage can be absorbed without transformation. What they ultimately demand is not more scandal, but a deeper questioning of the economic arrangements that make women’s bodies consumable in the first place.

The writer is a researcher and activist