Tl;DR: Driving the newsSaudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, the Gulf’s two most influential petro-powers, are sliding from strategic partnership into open rivalry – a shift that’s already reshaping the Yemen war, injecting new risk into cross-border commerce, and rippling across flashpoints from Sudan to the Horn of Africa.The fallout is no longer subtle. Where officials once papered over differences with “brotherly” rhetoric, the dispute has curdled into a public narrative war, bureaucratic friction for companies, and intensified proxy competition abroad.

“This isn’t a tactical disagreement,” HA Hellyer, a senior associate fellow at the Royal United Services Institute, told the NYT. “It’s a strategic split over what stability means in the Middle East.”Why it mattersThis rift is more than Gulf gossip. It’s a direct challenge to the region’s most important political and economic assumptions: that Riyadh and Abu Dhabi – however competitive – ultimately coordinate on security, energy and the big foreign-policy calls.That assumption underpins everything from investor confidence to war management in Yemen to the cohesion of the Gulf Cooperation Council and the stability of OPEC decision-making.If the rivalry deepens, the consequences could include:

- Higher geopolitical risk premiums for Gulf-linked investments and trade corridors.

- More intense proxy competition in fragile states where both already back opposing factions.

- A chill on cross-border business between two countries that have tried to sell themselves as safe, frictionless hubs for global capital.

Diplomats and executives are increasingly nervous about “what comes next,” as the Economist put it, with some privately drawing parallels to the 2017 Qatar crisis – even if a full embargo remains unlikely.The big pictureSaudi Arabia and the UAE have been aligned for decades. They are central members of the GCC and the oil producers’ cartel, and they fought together in Yemen against the Houthis after 2015.Their economic ties are deep: the Economist notes the UAE is Saudi Arabia’s fifth-largest export market for goods, while Saudi Arabia ranks ninth for the UAE, with bilateral trade around $31 billion annually. The Dubai-Riyadh route is among the world’s busiest international air corridors.But even when the partnership looked solid, cracks were visible:

- Their Yemen priorities diverged around 2018.

- OPEC tensions over production quotas flared in 2021.

- A broader economic rivalry intensified as Saudi Arabia tried to build a Dubai-like hub at home.

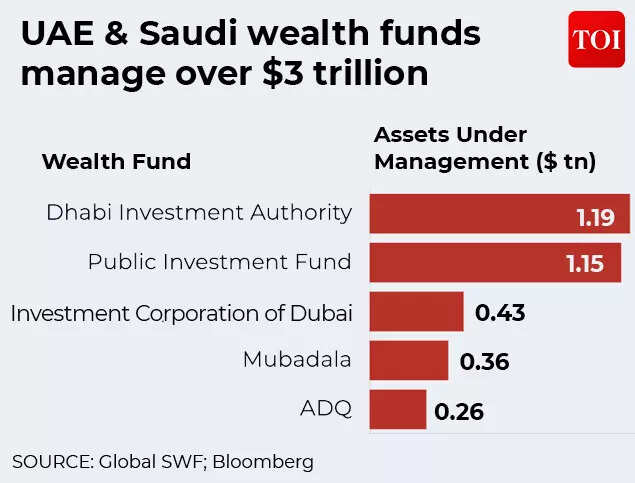

Foreign affairs argues that the rivalry’s economic engine is Saudi Vision 2030: Riyadh’s drive to attract capital, tourism, headquarters and talent at a scale that inevitably competes with the UAE’s established role as the Gulf’s commercial center. The contest isn’t just geopolitical – it’s a bid for primacy in finance, logistics, tech, tourism and influence.Neither side publicly frames it that way. But the incentives are hard to miss: a Saudi rise in non-oil sectors risks coming “at the cost of Emirati dominance,” as Foreign Affairs puts it, especially if global markets can’t sustain both at the same scale simultaneously.Zoom in: Yemen as the rupture pointThe current rupture burst into the open through Yemen, where Riyadh and Abu Dhabi once shared a military mission but increasingly backed different local power centers.According to the Economist, the relationship hit a new low in December when Saudi Arabia bombed an Emirati weapons shipment and accused the UAE of threatening its national security – despite describing the UAE as “shaqiqa” (“brotherly”) multiple times in an unusually strained diplomatic statement.The NYT reports that a UAE-backed separatist group launched an offensive in December to seize control of Yemen’s south – an area along key global trade routes – and Saudi officials responded by pushing back “forcefully,” declaring the kingdom would take responsibility for Yemen’s future.Reuters adds the most revealing detail: Riyadh is now trying to consolidate the anti-Houthi coalition by deploying political leverage and significant funds – in effect, replacing the Emirati role and asserting itself as the dominant external patron.“Saudi Arabia has cooperated with us and expressed its readiness to pay all salaries in full,” Yemeni Information Minister Muammar Eryani told Reuters.Reuters reports Saudi Arabia is budgeting nearly $3 billion this year for Yemeni salaries and stabilization, including roughly $1 billion earmarked for payments previously handled by Abu Dhabi – a major recurring commitment, especially as Riyadh faces budget pressures and expensive domestic mega-projects.Yasmine Farouk of the International Crisis Group captured the new dynamic bluntly: Saudi Arabia is prioritizing Yemen because “it is now the sole owner of this problem,” per Reuters.That “sole owner” posture is both strategic and reputational: Saudi Arabia wants a coherent anti-Houthi front, fewer rival command structures, and a stable border environment that doesn’t threaten Vision 2030 or investor confidence at home.Between the lines: It’s political – and personalIn the Gulf, policy disputes are often inseparable from leadership dynamics and status. Here, that’s central.Saudi Arabia, under its Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, sees itself as first among equals: it has Islam’s holiest sites, the largest GCC citizen population, and G20 weight. The Economist says a commentator close to the Saudi royal court recently described the UAE as a rebellious “younger sibling.”That framing infuriates Emiratis, who view their more diversified economy and militarily capable state as proof they no longer need to follow Riyadh’s lead. The NYT reports UAE elites grumble that Saudi Arabia is behaving like a domineering “big brother.”The widening gap shows up across multiple files:* Sudan: A sharp divergence after Sudan’s civil war erupted. Riyadh backed Sudan’s army; the UAE allegedly supported the Rapid Support Forces. The Economist notes the UAE acknowledges providing some early support but denies it continues.* Somalia/Horn of Africa: The Horn is a likely arena for further escalation, with Saudi and Emirati ties pulling in opposite directions and raising the risk of destabilization.* Syria: The Economist notes Saudi anxiety over Syria, where the UAE remains skeptical of Ahmed al-Sharaa, the ex-jihadist leader who took power after the Assad regime collapsed in 2024.* Israel and political Islam: The UAE normalized ties with Israel in 2020 and sees political Islam as an existential threat; Saudi Arabia has been more pragmatic – willing to tolerate some Islamist actors while prioritizing stability.These aren’t isolated disagreements – they reflect fundamentally different theories of order. Foreign Affairs says Saudi Arabia increasingly prioritizes predictability and calm to attract investment, while the UAE remains driven by preventing Islamists from gaining ground and by leveraging assertive interventionism.Zoom in: Business pressure without a formal embargoOne reason this rift matters globally: it hits the Gulf’s attempt to market itself as a stable magnet for capital.Bloomberg reports businesses are watching tensions closely, with firms quietly contingency-planning in case frictions intensify. Some UAE-based firms report problems securing Saudi business visas, according to people familiar with the matter, though a Saudi official told Bloomberg: “There’s no change regarding visa regulations and procedures for people residing in the United Arab Emirates, and the number of issued visas didn’t change.”Even without formal measures, the perception of informal obstacles can be enough to rattle decision-making – especially when Saudi Arabia is simultaneously pushing a “regional headquarters” policy designed to pull multinational offices from Dubai to Riyadh.At stake, Bloomberg notes, is roughly $22 billion in trade between the two largest Gulf economies – and broader confidence as both pitch themselves as global finance hubs backed by sovereign wealth funds with trillions under management.

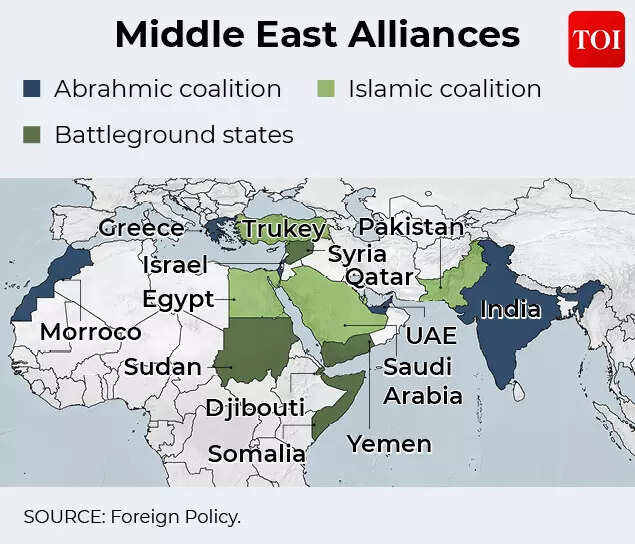

Zoom in: The Israel angle and the Saudi media turnThe Wall Street Journal ties the feud to a visible Saudi media shift: more aggressively anti-Israel rhetoric that also attacks the UAE’s alignment with Israel under the Abraham Accords.A Saudi editorial in Al Riyadh declared: “Wherever Israel is present, there is ruin and destruction,” per the WSJ, while a cleric at Mecca’s Grand Mosque said: “Oh God, deal with the Jews who have seized and occupied, for they cannot escape your power,” in a sermon cited by the WSJ.The WSJ reports Saudi columnist Ahmed bin Othman Al-Tuwaijri wrote: “The impostor from Abu Dhabi believes that the shortest path to avenging past grudges and healing the state of jealousy and feelings of inferiority toward the Kingdom is by throwing oneself into the arms of Zionism and accepting that the Emirates become the Israeli Trojan horse in the Arab world.”The politics are delicate. Saudi Arabia’s embassy in Washington told the WSJ the kingdom rejects antisemitism and remains open to normalization with Israel if there is a commitment to Palestinian statehood. But the public temperature matters: it shapes what normalization looks like – and whether it’s even feasible.Beyond the Gulf: How India and Pakistan figure in the Saudi-UAE rivalryThe Saudi-UAE split is no longer confined to the Gulf: It is increasingly entangled with India and Pakistan.Foreign Policy reports that the region is crystallizing into two loose camps, with the UAE and Israel at the center of what it calls an “Abrahamic” alignment that extends outward to include India. That bloc, the magazine argues, seeks to “reconfigure the region through military power, technological collaboration, and economic integration,” leveraging frameworks such as I2U2 and the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor.

On the other side, Foreign Policy describes an emerging counterweight led by Saudi Arabia, alongside Turkey and Pakistan – an “Islamic coalition” oriented toward sovereignty and counterbalancing what it views as destabilizing interventionism.That dynamic has become more explicit in recent months.Saudi Arabia and Pakistan signed a Strategic Mutual Defence Agreement in September 2025. The agreement signaled that Saudi Arabia was deepening military ties eastward at the very moment its trust in Abu Dhabi was eroding.Meanwhile, as news spread of a potential Saudi-Turkey-Pakistan security alignment, Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed made a high-profile visit to India, signaling Abu Dhabi’s intent to fortify its own strategic footprint with New Delhi.Foreign Policy frames India as giving the UAE-Israel axis “strategic depth that extends well beyond the Middle East itself,” particularly through technology and logistics integration. That matters because India is both a rising economic power and a maritime actor with growing stakes in the Red Sea and Gulf shipping corridors – the same arteries affected by Saudi-Emirati competition in Yemen and the Horn of Africa.Pakistan, by contrast, occupies a different role. It is a long-standing Saudi security partner, and its inclusion in a more formal Saudi-led defense framework sends a message: Riyadh is building external security buffers independent of Abu Dhabi’s network.What’s nextThe immediate question is whether mediation can halt the slide.The Economist reports Qatar has tried to mediate – an ironic twist given the UAE and Saudi Arabia once helped blockade Qatar – while Bahrain, Egypt and Turkey are also working diplomatic angles.President Donald Trump, never shy about his deal-making brand, said: “I can settle it very easily,” on February 16, per the Economist. Yet diplomats quoted there suggest the administration is wary of wading into a dispute between two allies whose ties to Trump-world business networks create extra sensitivity.In the near term, three scenarios look most plausible:1. Managed rivalry, quiet reset: Backchannel diplomacy cools rhetoric, and the two sides compartmentalize disputes – especially to reassure investors.2. Proxy escalation: Sudan, Somalia and the Horn become sharper arenas for competition, raising conflict intensity and humanitarian risks.3. Economic “frictionization”: Not a blockade, but more regulatory pressure, slower visas, customs delays and competing rules – enough to reshape how multinationals structure Gulf operations.Mohammed Baharoon, head of a Dubai research center, told the NYT that ambiguity is what makes this rift dangerous: “In this case, there is no list of demands.” That absence of an off-ramp increases the risk of miscalculation.(With inputs from agencies)